Slang for “dropping documents,” doxing (also spelled doxxing) typically occurs when someone collects another’s private personal information, such as a home address, contact information or social security number, and subsequently broadcasts or “outs” that information to the public without permission. Crash Override Network (a task force made up of people who have previously been targeted) describes doxxing as a “tactic of mobs of anonymous online groups” whose goal is to scare targets by exposing their personal information online. While your personal information may have nothing to do with them, their objective is to make you fearful about how it could potentially lead to your own victimization. To be sure, it might be prompted by seeking revenge for a perceived affront, or to bring attention to someone who has previously operated under the mask of anonymity or pseudonymity – or might simply be done for “kicks.” The scariest part, of course, is that once your private contact details are put out there electronically, it’s difficult to get them taken down – and is therefore available for anyone with malicious or reckless motives to see, find, and use against you.

Doxing first arose approximately ten years ago, originally used by journalists to refer to “deep investigative reporting.” As a result, there appears to be a disconnect of sorts between malicious intrusions into someone’s private personal life, and honest journalism. And in recent months, we have seen this phenomenon occur increasingly often both in small circles (among a few of my university students) and large (in stories that have made national news). Below I discuss some prominent examples that highlight the nature of this problem, as they demonstrate the emotional and psychological toll it can take on its targets and because it truly can happen to anyone – given the right circumstances.

Doxing in the News

Cecil the Lion: In July of 2015, the Sun Sentinel reported that a lion named Cecil was “lured from a protected national park in Zimbabwe and killed in an illegal hunt.” The Telegraph, a prominent British newspaper, then disclosed the identity of the hunter involved: Walter Palmer, a dentist from Minneapolis, Minnesota. Shortly after Palmer’s identity was released, he became the subject of internet hate, being called a “scumbag,” “disgrace to humankind” and a “detriment to our species as a whole.” His address, website and work phone number were “plastered everywhere” and his work website was taken offline as a result. Of his own volition, he took his Facebook page down as well. Not only has Palmer had his life threatened online, he has also faced protests outside his office in Minneapolis. Moreover, his vacation home in Florida was also vandalized, as individuals spray-painted the words “lion killer” on his garage door. One particular online commentator remarked, “there is no fury like the impulsive, knee jerk fury of social media clicktivists who respect no boundaries or property but their own.”

Ashley Madison: Ashley Madison is an online dating site specifically oriented towards those interested in “extramarital romance and sex,” and is arguably the “most famous name in infidelity and married dating.” Like Tinder or other online environments in which relationships and hookups are fostered, users on this site can browse through the profiles of others who are seemingly looking to have an affair.

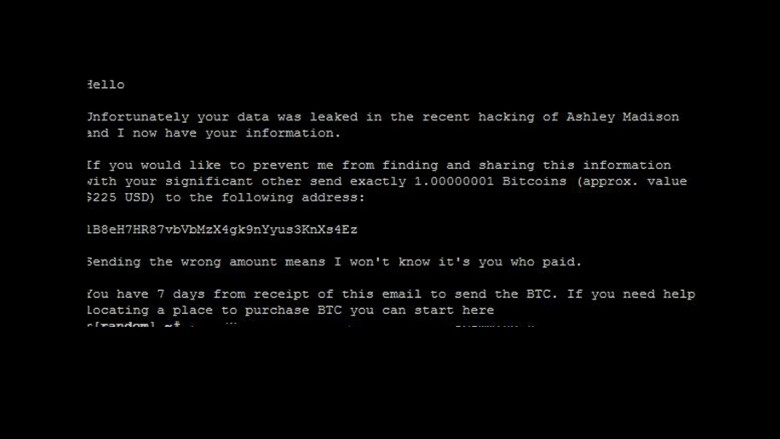

Recently, a group of hackers called the “Impact Team” ordered Ashley Madison to permanently take down the site, alleging questionable morals and fraudulent business practices. When it did not comply, the hacker group released about ten gigabytes of user data from the site. This included around thirty million Ashley Madison user e-mail addresses. Approximately half of those were military and government addresses. Users’ personal information, such as names, addresses, phone numbers and sexual preferences and interests, were also made public. Victims of the data leak quickly became concerned about public embarrassment, shame, and their partners finding out. Recently, a pastor in New Orleans committed suicide after being outed in this way; he specifically mentioned Ashley Madison in his suicide note. Investigators in Toronto are also examining two suicides that may be linked to the doxing from this breach, and law enforcement around the world are looking into emails attempting to extort victims by requiring payment in exchange for not further sharing the information.The fallout from this hack and the consequent public reveal are clearly leaving raw tragedy, devastation, and upheaval in its wake.

Reddit: In 2012, a writer named Adrian Chen from the online news site “Gawker” revealed the identity of Michael Brutsch, a Reddit user, through doxing. Reddit, which was founded in 2005, is a “bulletin board” themed site filled with news and entertainment where members can post almost anything by topic. Using the screenname “Violentacrez,” Brutsch was well known for distributing pictures of girls younger than 18 years old in bikinis, and for making inappropriate remarks relating to racism, porn, incest and more. Once his identity was revealed, Brutsch was fired from his programming job and subsequently began accepting donations through PayPal. The public’s reaction was two-fold: some journalists supported Chen’s bravery in exposing Brutsch’s identity, while the Reddit community disfavored his actions, because they like to be anonymous when using the site.

Bitcoin: Similarly, the identity of the man presumably behind Bitcoin – Satoshi Nakamoto – was exposed when he was doxed. Bitcoins can be used for “online transactions between individuals” with no transaction fees involved with using this service and no need to supply one’s real name. This act of doxing has ignited the debate over whether it is appropriate to reveal the names of people who strive to remain anonymous. There are arguments to be made on both sides. One argument is that exposing the identity of an inventor may encourage consumers to trust their product or business. Conversely, remaining anonymous allows the individual to not have to worry about his personal safety and, admittedly, to more freely participate in activities that are new and subject to scrutiny and questioning.

A Form of Cyberbullying?

It has been argued that hackers use doxing as a “tactic of harassment,” and therefore the actions are somewhat related to cyberbullying. The goal of those who seek, find, and then release personal information of others is ostensibly to bully or scare targets by destroying their sense of privacy and rendering them vulnerable to victimization by future harassers. For instance, a bullying aggressor might make use of your personal information by ordering multiple pizzas (that you never ordered or wanted!) for delivery at your home address. Another tactic is called “swatting,” and occurs when someone anonymously calls the police with a false threat (like a hostage situation) and uses your address, causing deployment of the police SWAT team to show up at your house armed and ready for violent action. This has most often stemmed from online gaming arguments, and has even left victims injured by police.

Justin and I were recently discussing whether doxing can serve a deterrent effect if targets or witnesses outed and then publicly shamed those who participated in bullying others. We saw this happen earlier this year when Curt Schilling’s daughter was harassed online, and he took the time to publicize the identities of two men whose online hate was particularly vicious. Through this form of vigilante justice, both men suffered severe reputational fallout: one was fired from his job with the New York Yankees, and the other was suspended from his community college. On one hand, we could argue that it “serves them right,” but on the other we know that any one of us could make a similar mistake with our words and actions and deserve some grace if we are remorseful. I do believe the aggressors in this situation will be deterred in the future, but I also feel personally that “two wrongs don’t make a right” and that ethically, doxing is fundamentally wrong because expectations of privacy are violated with malice aforethought.

How to Prevent Doxing

Considering the extent to which most of us have seeded the Internet unknowingly, naively, or intentionally with personal information (bank account details, credit card numbers, birth dates, addresses, phone numbers, and various other private nuggets of our lives), the reality is that anyone can fall prey to doxing. Justin and I marvel at the brashness with which some of our Facebook friends regularly post inflammatory and emotionally-charged status updates related to politics, religion, or social justice issues, and often discuss how such posts could really set someone else off who reads it. That reader may become antagonistic and even maliciously motivated, and if they are in your social network, they already have access to a lot of your personal information in your profile. The bottom line is they can do anything with those details. Also, public repositories online such as your county records database, business licenses databases, and search sites like Zabasearch, MyLife, Pipl, PeekYou, and Spokeo contain a surprising amount of personal data about you that might equip another person to harass, bully, stalk, or out you.

All things considered, you should use extreme discretion when voluntarily giving out any personal information to various sites online. If possible, erase your address from any personal accounts or sites where it already exists. Furthermore, keep Googling your name and even your contact information on a regular basis to make sure that it is not showing up on various Internet sites without your permission. As a related point, Justin and I own various domain names, and have to provide a physical mailing address when registering them at domain registrars. We use addresses that are not our actual homes for obvious privacy and safety reasons, but we know many do. If you own a domain, make sure you look up your “Whois” information to see what personal contact information is available for others to access. If you need to use your home address and details, you can pay extra for domain privacy services at your registrar to mask those entries, or we recommend purchasing a P.O. Box and using that address instead. You can even set up a Google Voice number and use that instead of your home or cell phone number.

Finally, take the time to go through your friends and followers and eliminate those you don’t really know or trust – particularly on social media sites (Facebook for sure, and possibly Instagram) where a lot of information gathering about you and your lifestyle can occur. And of course make sure your privacy settings are as locked down as you want them to be. I know it is easy to think that you don’t have anything to worry about, and nothing is probably going to happen to you (we all often share that “invincibility complex”!). However, it’s worth remembering that all of the aforementioned individuals who were doxed probably thought the same thing as well – and look what happened to them.

The post Doxing and Cyberbullying appeared first on Cyberbullying Research Center.