With First Lady-Elect Melania Trump mentioning cyberbullying would be the major social issue she would like to prioritize and tackle during her husband’s U.S. presidential administration, everyone in my line of work has been buzzing about what that could possibly mean. These last eight years have brought good progress with anti-bullying and anti-cyberbullying efforts by the White House, Office of Civil Rights, and U. S. Department of Education (among others). And we’re just hoping that there will be continued and even increased support and contributions from the highest office in the land. That is, without a doubt, tremendously exciting for all of us.

As such, friends and colleagues have been proposing some ideas for the new administration to consider in this area. For instance, Family Online Safety Institute (FOSI) CEO Stephen Balkam has called for a Chief Online Safety Officer, a cross-agency Working Group, an annual Online Safety Summit at the White House, and a $25-million-dollar Research and Education Fund. A recent CNN article summarized recommendations from experts including Carrie Goldman, Matthew Soeth, Anne Collier, Michele Borba, and Alan Katzman who emphasized empowering bystanders, calling attention to the positive things that kids are doing, and focusing more on social-emotional learning and “cyber civics.”

I like these ideas. They are the standard suggestions people in this space have been offering for years (including us). And they really can matter. But we should dive even deeper. So far, we haven’t seen anything resembling a plan of action from the First Lady-Elect, but perhaps one will be released in the next month or two. Accordingly, we’d like to offer our perspectives in case they can help.

Our Work

Here at the Cyberbullying Research Center, Justin and I have focused on conducting research to inform both policy and practice, but spend an equal amount of time on the front lines of the problem. We work “hands-on” with tens of thousands of individuals every year (educators, mental health professionals, law enforcement officials, youth-serving organizations, parents, and kids) to help them identify, prevent, and respond to all forms of adolescent interpersonal harm, but with a particular focus on cyberbullying.

And so based on the last fifteen years in the trenches, I want to share just two key recommendations that I believe our federal government should follow over the next four years (starting as soon as possible). I’ll be short and to the point here, but you can circle back if you’d like more even information, citations, or details on each point.

Give Schools Evidence-Based Guidance

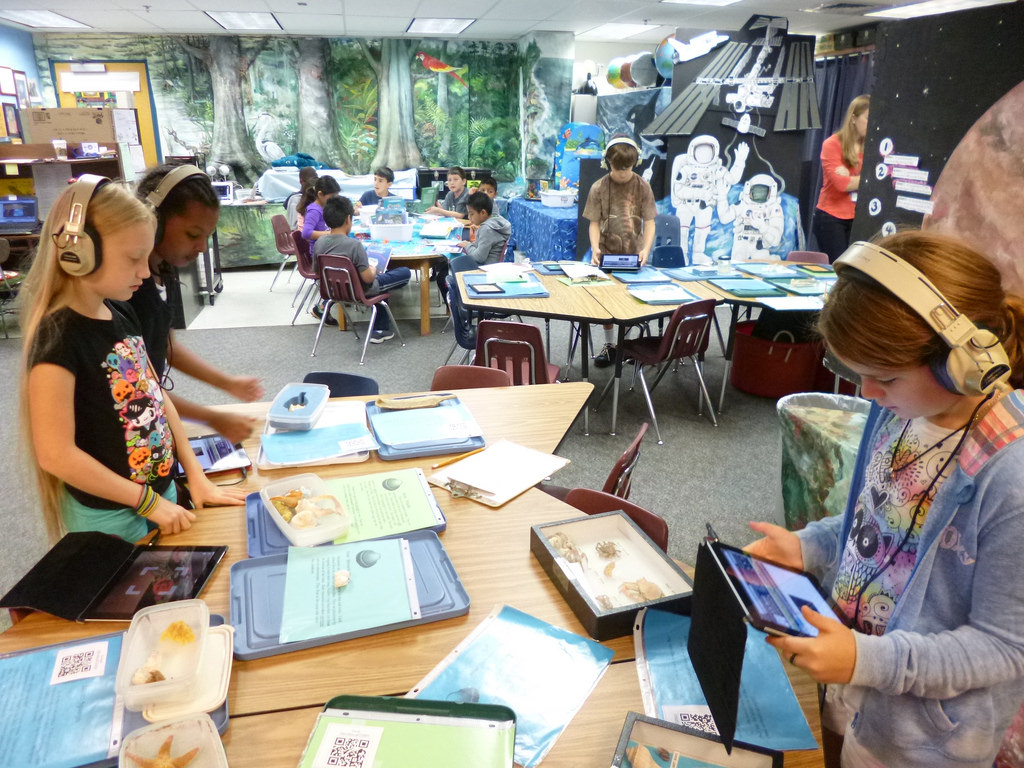

Schools across each state – within each district across each region – are often left to figure out from trial and error (and from random Google searches) what sort of strategies they should implement to bear fruit in addressing cyberbullying. We go into schools all the time and administrators simply don’t know what they should do (and not do) to really make a difference.

For example, when it comes to student cell phones and technology use, some schools are completely prohibitive, others are completely permissive, and still many others are somewhere in between. Again, there is so much unnecessary (and unproductive) variation even in the same county! Schools differ widely with regard to filtering and blocking, training of faculty and staff, training of students (and parents!), policies in place, accountability, reporting systems, knowledge of legal, social, and reputational consequences, search and seizure issues, and so much more.

School desperately need some clear, practical guidance from the federal government as to what is expected within a 21st century school in America to reduce online (and offline) harassment and promote peer respect, tolerance, and kindness. It’s 2017, for crying out loud. They need explicit counsel in this area, and it is high time we provided it to them.

How To Address Cyberbullying

When it comes to school-based programming, here again it is clear that schools are all over the place. I do realize that many communities are simply underfunded and underequipped. But honestly, by 2017, you would have hoped that we could provide informed, research-based guidance to every school from a federal level about what works, and what doesn’t (and a bottom-line respectable amount of resources to provide training, personnel, technology, and research within schools to identify best practices).

Schools desperately care about stopping all forms of bullying, and are trying a variety of things – from random assembly speakers, to random documentaries and “teachable moment” YouTube videos, to random curricula they hear about from unsolicited emails or tweets, to random programs that capitalize on a quick emotional reaction but fail to effect meaningful, long-lasting change that carries on not only through the school year, but beyond.

This approach is like throwing a random bunch of gummy worms at a wall to see which will actually stick. At best, it is inefficient, and at worst it is doing more damage that good (as kids will tune out and stop listening to your voice – a voice that truly has the power to positively change their lives).

So, you ask, what are the most promising approaches? What should be done in every school, according to research?

- Resilience programming [1-3]

- Social norming [4-7]

- School climate efforts [8] [9-12]

- Positive behavior supports [13-15]

- Social and relational skillsets [16-18]

- Problem-solving and decision-making techniques [19-22]

- Emotional intelligence, self-awareness, and self-management [23-27]

- Empathy training [28-31]

It might feel like a “kitchen-sink” model, but they are all interconnected and highly relevant. And note that none of these are dependent on, or inextricably linked with, technology itself. Social media, phones, tablets, Internet of Things (IoT) devices – they are not the problem; they are only tools that can be wielded in helpful or harmful ways. The above programs have helped meaningfully address a variety of problem behaviors at school. We strongly believe they will also positively impact online behaviors (of course, more research is required to make sure the benefits persist).

Everyone Has a Role to Play, Including the Federal Government

To be sure, there are many players who necessarily must be involved in addressing cyberbullying. Technology companies (we work with many in this space) are increasingly doing their part (thankfully) through in-app reporting, blocking, and other safety mechanisms. Parents, we hope, are stepping up and realizing their role to teach and model the competencies all youth need. Mental health specialists (counselors, general practitioners, social workers) gradually are learning and understanding what they should do through professional development opportunities. The federal government may work with these constituent groups, but I strongly believe it has more sway and influence on our public educational system, and the power to revolutionize its impact on students. Schools must be where our attention and energies are focused, to most broadly and profoundly reach our youth – today, tomorrow, and beyond.

Citations

- Benard, B., Applications of resilience, in Resilience and Development. 2002, Springer. p. 269-277.

- Ginsburg, K.R. and M.M. Jablow, Building resilience in children and teens. 2005: Am Acad Pediatrics.

- Theron, L.C. and P. Engelbrecht, Caring teachers: teacher–youth transactions to promote resilience, in The Social Ecology of Resilience. 2012, Springer. p. 265-280.

- Crick, N., M. Bigbee, and C. Howes, Gender differences in children’s normative beliefs about aggression: How do I hurt thee? Let me count the ways. Child Development, 1996. 67: p. 1003-1014.

- Craig, D.W. and H.W. Perkins. Assessing Bullying In New Jersey Secondary Schools: Applying The Social Norms Model To Adolescent Violence. in National Conference on the Social Norms Approach. 2008. San Francisco, CA.

- Perkins, H.W., D.W. Craig, and J.M. Perkins, Using social norms to reduce bullying: A research intervention among adolescents in five middle schools. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 2011. 14(5): p. 703-722.

- Osanloo, A. and J. Schwartz, Using social norming, ecological theory, and diversity based strategies for bullying interventions in urban areas: A mixed methods research study. Urban school leadership handbook, 2015: p. 199-210.

- Hinduja, S. and J.W. Patchin, School Climate 2.0: Preventing Cyberbullying and Sexting One Classroom at a Time. 2012, Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin; 2012.: Sage Publications (Corwin Press).

- Freiberg, H.J., ed. School climate: Measuring, improving, and sustaining healthy learning environments. 1999, Falmer Press: London.

- Welsh, W.N., The effects of school climate on school disorder. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 2000. 567: p. 88-107.

- Orpinas, P. and A.M. Horne, Bullying prevention: Creating a positive school climate and developing social competence. 2006: American Psychological Association.

- Eliot, M., et al., Supportive school climate and student willingness to seek help for bullying and threats of violence. Journal of school psychology, 2010. 48(6): p. 533-553.

- Waasdorp, T.E., C.P. Bradshaw, and P.J. Leaf, The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: A randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 2012. 166(2): p. 149-156.

- Pugh, R. and M. Chitiyo, The problem of bullying in schools and the promise of positive behaviour supports. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 2012. 12(2): p. 47-53.

- Bradshaw, C.P., Preventing bullying through Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS): A multitiered approach to prevention and integration. Theory Into Practice, 2013. 52(4): p. 288-295.

- Greenberg, M., et al., School-based prevention: Promoting positive youth development through social and emotional learning. American Psychologist, 2003.

- Espelage, D.L., C.A. Rose, and J.R. Polanin, Social-emotional learning program to reduce bullying, fighting, and victimization among middle school students with disabilities. Remedial and special education, 2015. 36(5): p. 299-311.

- Durlak, J.A., et al., The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions. Child development, 2011. 82(1): p. 405-432.

- Champion, K., E. Vernberg, and K. Shipman, Nonbullying victims of bullies: Aggression, social skills, and friendship characteristics. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2003. 24(5): p. 535-551.

- Rubin, K.H., L.A. Bream, and L. Rose-Krasnor, Social problem solving and aggression in childhood. The development and treatment of childhood aggression, 1991: p. 219-248.

- Cassidy, T., Bullying and victimisation in school children: The role of social identity, problem-solving style, and family and school context. Social Psychology of Education, 2009. 12(1): p. 63-76.

- Warden, D. and S. Mackinnon, Prosocial children, bullies and victims: An investigation of their sociometric status, empathy and social problem‐solving strategies. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2003. 21(3): p. 367-385.

- Shields, A.M., D. Cicchetti, and R.M. Ryan, The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and social competence among maltreated school-age children. Development and Psychopathology, 1994. 6(01): p. 57-75.

- DeWall, C.N., et al., Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental social psychology, 2007. 43(1): p. 62-76.

- Garner, P.W. and T.S. Hinton, Emotional display rules and emotion self‐regulation: Associations with bullying and victimization in community‐based after school programs. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2010. 20(6): p. 480-496.

- Mayer, J.D., R.D. Roberts, and S.G. Barsade, Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 2008. 59: p. 507-536.

- Kokkinos, C.M. and E. Kipritsi, The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Social psychology of education, 2012. 15(1): p. 41-58.

- Steffgen, G., et al., Are cyberbullies less empathic? Adolescents’ cyberbullying behavior and empathic responsiveness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 2011. 14(11): p. 643-648.

- Ang, R.P. and D.H. Goh, Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 2010. 41(4): p. 387-397.

- Jolliffe, D. and D.P. Farrington, Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggressive behavior, 2006. 32(6): p. 540-550.

- Gini, G., et al., Does empathy predict adolescents’ bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive behavior, 2007. 33(5): p. 467-476.

Image sources:

bit.ly/2hxaGH3

bit.ly/2gYuSxq

bit.ly/2i6oMjz

bit.ly/2ibDAt0

The post The Priority for Cyberbullying Prevention in 2017 and Beyond appeared first on Cyberbullying Research Center.